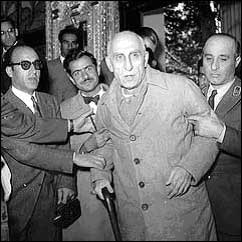

Iran 1953

Iran’s deposed prime minister, Mohammed Mossadeq, at his trial

Operation TPAJAX was the CIA-sponsored overthrow of Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadeq in Iran . For some time, Iran had been considered by the U.S. as a British responsibility, if not an actual client state. It was a British-backed coup that had made it possible for the Pahlavi dynasty to be founded in the 1920s; then, during World War II, the British and Soviets invaded the country and deposed the Shah, putting his son on the throne. Iran 's oil industry was entirely in British hands and there was a large and active U.K. embassy in the middle of Tehran . By contrast, although the United States also had a presence in Iran , providing economic advice and military training, the scale of its activities was, at least through 1952, considerably less than that of Britain . In particular, the U.S. had no oil investments in Iran.

As the cold war intensified, U.S. officials grew increasingly concerned at the prospect of Iran falling under communist domination. Iran bordered on the Soviet Union, which took until May 1946 to withdraw its troops (in part as a result of U.S. pressure) and tried to establish autonomous republics in the country's northern provinces . Within Iran , the Tudeh party identified openly with the U.S.S.R. and received considerable electoral support. The U.S. was less than sanguine about the British ability to cope with this situation and so, starting around the time that the U.S. was taking over from them in Greece, it renewed the military training agreement and also began to extend the policy instruments it had developed for Europe to Iran: it established a CIA station in Tehran, organized a “stay-behind” network to provide for resistance in the event of a Soviet invasion, set up a covert propaganda and political action operation designed to undermine the Tudeh party, included Iran in the Mutual Defense Assistance Act of 1949 and then the Mutual Security Act of 1951, and supported a World Bank loan and approved another loan from the ExIm Bank.

From Washington 's perspective, the situation began to spin out of control in 1951. In the spring of that year, the parliament passed legislation nationalizing the oil industry and the shah was constrained by political pressure to name Mossadeq, the principal architect of the legislation and staunch anti-imperialist, as prime minister. He took power at the head of a heterogeneous coalition called the National Front but, on issues such as nationalization, was also supported by Tudeh and an Islamic fundamentalist party. The British were aghast at this turn of events, all the more so as they had thought themselves able to pull strings behind the scenes in parliament; and they immediately began trying various strategies, from diplomatic pressure to economic sanctions and covert action (they even explored an invasion) to stop the nationalization, if need be by booting Mossadeq out of office. The Americans were no less concerned, but for different reasons. They thought that if the British-Iranian dispute continued, it would only increase the chances of “the loss of Iran to the free world ... through an internal communist uprising, possibly growing out of the present indigenous fanaticism or through communist capture of the nationalist movement.” Hence the U.S. tried for months, at the highest levels, to bring the two sides to a compromise.

All this was to no avail. By the summer of 1952, U.S. officials had begun to see Mossadeq as the principal obstacle to an agreement with the British. At the same time, the internal political situation was polarizing, in part because of British covert efforts. Mossadeq's coalition was already disintegrating when, for various reasons, he began to purge the military, which opened up the possibility of a coup by disaffected officers. This the British encouraged but the plot was discovered and broken up in October before it could be carried out; for good measure, Mossadeq broke diplomatic relations with Britain and expelled all its officials. Now the British turned to the U.S. for help, sending the former head of its covert operations in Tehran to Washington . He arrived to find the Truman administration worried that by eliminating his noncommunist rivals, Mossadeq had become too isolated to keep the communists out of power “for an extended period of time” and that “Iran was in real danger of falling behind the Iron Curtain.” Logically, of course, the U.S. could have decided to help Mossadeq by circumventing the British oil embargo and making a major aid grant to Iran, but these policies – which were in fact pursued or contemplated by both Truman and Eisenhower – never worked out for the simple reason that they were premised on at least some continued British role in the oil industry, something that Mossadeq flatly refused. In effect, the U.S. ties to Britain and its fear of communism in Iran led it to classify Mossadeq's government as likely to “turn against the U.S. ,” i.e., as an enemy regime in the making. A coup was approved in the spring and the CIA used its propaganda assets, the British ties to opposition politicians, the U.S. mission's links with military officers, and generous sprinklings of cash (to assorted religious figures, mob organizers – including one nicknamed “the brainless” – and the shah's sister) to overthrow Mossadeq and replace him with a pro-British general. When the dust settled, the U.S. had a new client state and, as a bonus, forty percent of its oil exports. 1

1) NSC 107/2, “The Position of the United States With Respect to Iran,” 27 June 1951, par. 2; NSC 136/1, “United States Policy Regarding the Present Situation in Iran,” 20 November 1951, par. 2; both ProQuest (2005); Wilber (1954: iii); Acheson memo to Eden, 22 November 1952, in State to London, s.d., FRUS 1952-1954 , vol. 10: doc. 241; also docs. 234, 236, 311; Gasiorowski (1987; 1991: chs. 2-3; 2004); Gavin (1999); Kinzer (2003); Louis (2004); Byrne (2004). The FRUS volume on Iran is woefully incomplete, containing nothing on the CIA's activities; at the time of this book's writing it was being reedited, presumably with an eye to incorporating some CIA materials. The Wilber study, by one of the U.S. organizers of the coup, was only released in 2000.